6 Identity Over Time

We will now explore the question of persistence. Material objects are temporally extended by which we mean that they exist at more than one time. But what exactly is for a material object to exist at one time and then at another time? More generally, we will be concerned with the question of how best to make sense of persistence.

There is no mystery as to how to understand spatial extension. You would presumably not be moved by the purported puzzle below:

- I’m found in a certain spatial region \(R\).

- I’m found in a spatial region \(S\) which is disjoint from \(R\).

- Therefore, one and the same object is found in two disjoint spatial regions.

For there is a simple gloss of these facts:

- One of my parts is found in a certain spatial region \(R\).

- One of my parts is found in a spatial region \(S\) which is disjoint from \(R\).

- Therefore, one and the same object has parts found in two disjoint spatial regions.

Indeed, to be spatially extended is to have parts found in disjoint regions.

But temporal extension appears to be different:

- I have been found in the twentieth century.

- I have been found in the twenty first century.

- I have been found in two centuries, which are disjoint temporal intervals.

And, on the face of it, we may add:

- All of me has been found in the twentieth century.

- All of me has been found in the twenty first century.

- All of me has been found in two centuries, which are disjoint temporal intervals.

That would appear to suggest a difference between persistence and spatial extension.

To persist is to be found or to be present at more than one time; to exist over time; to survive from one time to another, etc.

To be found or present at one time is not to be entirely found or entirely present at that time … each of you is found at the present time despite the fact that you are not entirely inside that temporal moment.

To be found at one time, to exist at one time, to be present at one time will all eventually be analyzed in terms of a primitive locative relation.

The key thought is that to persist is to be present throughout an extended temporal interval, which means that one is not confined to a single instant. To be confined again will require further analysis in terms of a primitive locative relation.

6.1 Perdurance and Endurance

A first pass at the distinction is due to David Lewis:

To endure is to be wholly present at more than one time within a certain interval.

To perdure is to be partly present at each moment of an interval and to be wholly present at only at the whole interval

Here is David Lewis in (Lewis 1986):

Let us say that something persists iff, somehow or other, it exists at various times; this is the neutral word. Something perdures iff it persists by having different temporal parts, or stages, at different times, though no one part of it is wholly present at more than one time; whereas it endures iff it persists by being wholly present at more than one time.

Perdurance is modeled after spatial extension. To be spatially extended is to be partly present at each point of a spatial region, and to be wholly present at the whole region. The thought is that temporal extension is akin to spatial extension.

6.1.1 Perdurance

To perdure is to be partly present at multiple times.

Events appear to perdure. They have temporal extent and temporal parts of the event occupy briefer time periods, e.g., this course consists of several temporally extended lectures over the course of a week.

Temporal parts are segments or stages of a material object along a temporal dimension. Consider the spatiotemporal region I occupy in the four-dimensional manifold. Now, consider a spatiotemporal region, which shares exactly the same spatial boundaries but has a more limited temporal extent, e.g., from 2000 to 2010. A temporal part of mine would be a material object, which would exactly occupy that spatiotemporal region.

To use Ted Sider’s illustration in (Sider 2003), consider your own life:

Think of your life as a long story. … Like all stories, this story has parts. We can distinguish the part of the story concerning childhood from the part concerning adulthood. Given enough details, there will be parts concerning individual days, minutes, or even instants.

According to the ‘four-dimensional’ conception of persons (and all other objects that persist over time), persons are a lot like their stories. Just as my story has a part for my childhood, so I have a part consisting just of my childhood. Just as my story has a part describing just this instant, so I have a part that is me-at-this-very-instant.

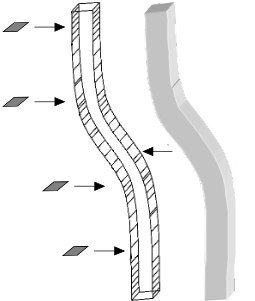

You, for the four-dimensionalist, are nothing but an aggregrate of person stages. Here is an illustration of perdurance from (Gilmore, Calosi, and Costa 2024):

There is a qualification. The illustration simply presupposes that time intervals are composed of time instants, and that no matter what some instantaneous temporal parts may be, they themselves compose another temporal part. But one may be a perdurantist and leave open whether there are time instants.

6.1.2 Endurance

To endure is to be wholly present at multiple times.

I have been wholly present in the twentieth century.

I have been wholly present in the twenty first century.

I have been wholly present in two centuries, which are disjoint temporal intervals.

But what exactly is for me to be wholly present somewhere? One may be tempted to give the following gloss:

All of my parts have been found in the twentieth century.

All of my parts have been found in the twenty first century.

All of my parts have been found in two centuries, which are disjoint temporal intervals.

One common model of endurance regards persistence as akin to travel through time. To travel through time is to occupy different moments in time in its temporal entirety. This is parallel to a view of travel through space in terms of the occupation of different places in space in its spatial entirety. Unfortunately, the analogy breaks down, since travel through space presupposes time as a dimension of variation. There is no similar dimension of variation one may appeal to in order to make sense of travel through time.

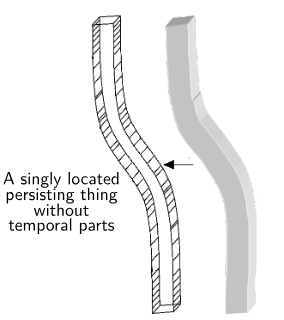

The picture that emerges is one of a three-dimensional object in a certain locative relation to different time instants. The illustration below appears in (Gilmore, Calosi, and Costa 2024).

Ted Sider objects to this model of endurance in (Sider 2003) on the grounds that material objects often change their parts. Since I have often gained new parts over the years, it is not true that all of my parts could be found back in the twentieth century. So, it is false that I have been wholly present in the twentieth century, since some of the newer parts have not be found there.

Or consider my car, which, we may suppose, has lost a mirror over the course of the years. Is the mirror part of the car? If it is, notice that while the mirror is not present now, the car appears to be. So, it is now wholly present now.

Sider briefly considers a reply on behalf of the endurantist. Maybe the relation of part to whole should itself taken to be relative to a time in which case would rephrase the statements as follows:

All of my parts in the twentieth century have been found in the twentieth century.

All of my parts in the twenty first century have been found in the twenty first century.

All of my parts in each century have been found in each century, even though the two centuries are disjoint temporal intervals.

True, but unremarkable. Even the perdurantist would agree to that gloss.

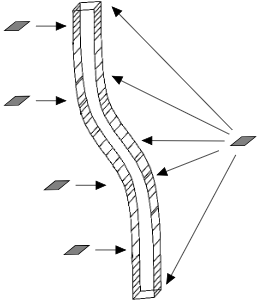

More recently, (Parsons 2007) has proposed another model for endurantism. To endure, for Parsons, is to be a temporally extended simple: to the extent to which I’m a temporally extended object without temporal parts, I’m wholly present now; all of my temporal parts are present now.

Consider the case of spatial location. To say that I’m wholly present in the room is presumably to say that all of my spatial parts are in the room. That would not be the case, for example, if I step over the threshold or stick my head out of the door. It may seem that to be wholly present in the room is much like to be entirely within the room, but there are exotic counterexamples to the identification. Consider the case depicted by Figure 5a in (Gilmore, Calosi, and Costa 2024):

The object \(o_1\) in the diagram is an extended simple, which is wholly present in both \(r_1\) and \(r_2\). It is wholly present in \(r_1\) because all of its spatial parts are present at \(r_1\), and likewise for \(r_2\). That is:

- All spatial parts of \(o_1\) are present in \(r_1\)

- All spatial parts of \(o_1\) are present in \(r_2\)

It is, however, not entirely within either \(r_1\) or \(r_2\). So, if there are extended simples, then no spatial part of them fails to be found at a region at which they are found. So, they are wholly present at every region at which they can be found.

Temporal location is not the same as spatial —or even spatiotemporal— location. If someone has been born at the same time instant as another person have and comes to die at exactly the same time as that person, then they will have exactly the same temporal location even if we differ with respect to spatial location.

Let us return now to the case of temporal location. One may now gloss wholly present at a time or time interval similarly. To be wholly present now is for all temporal parts to be found now.

When we deploy the gloss to the case with which we started, we find:

All of my temporal parts have been found in the twentieth century.

All of my temporal parts have been found in the twenty first century.

All of my temporal parts have been found in two centuries, which are disjoint temporal intervals.

To say that my car is wholly present now is just to say that all of its temporal parts are present now, but notice that the mirror that used to be part of my car is not —and had never a claim to be— a temporal part of my car. Here is an illustration of the present model of endurance drawn from (Gilmore, Calosi, and Costa 2024):